Simon Littlejohn, a Field Technical Support Engineer and PicoScope user, looks at a Fiat Ducato with turbo under-boost and air flow meter drift.

When evaluating 2018, I instantly start thinking about all the diagnostic problems I had to deal with during the year. With this in mind, I wanted to share the biggest problem that I came across, which happened to be whilst helping a dealership.

The procedure

The vehicle in question was a 2016 Fiat Ducato 2.3 Euro 6 diesel van with 80,000 miles on it. It had had the parts cannon shot at it – a typical case for ScannerDanner (YouTuber) – and thanks to a Frank Massey video, I found the fault.

The vehicle had already had the following parts replaced: engine ECU, air flow meter, four injectors, intercooler, DPF, low and high-pressure EGR valve, EGR cooler, boost control valve and turbo; all new and genuine parts. In addition, the timing had been checked, the exhaust swapped, and the air intake had been checked for leaks. These changes had all taken place despite there being no faults found and no improvement on the vehicle, which added up to over £10,000 in parts alone!

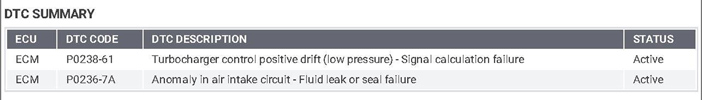

The vehicle had an ongoing concern; flagging an error for turbo under-boost and air flow meter drift (Fig.1). However, it only flagged this error once every 400 miles or so, which meant that the fault was very difficult to reproduce. It would normally set at about 30% throttle and not full load, as if it had a leak or a blockage.

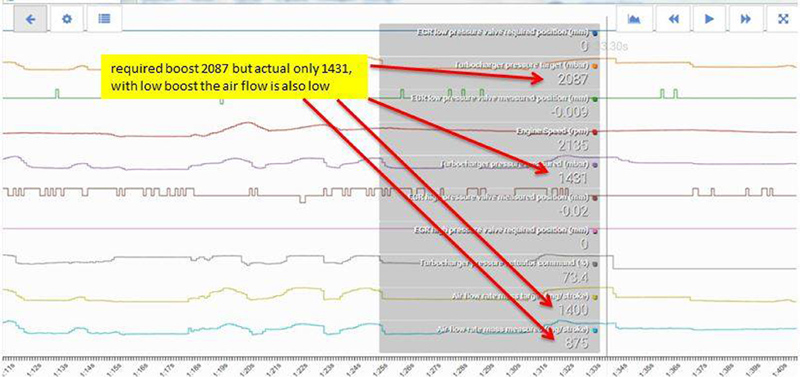

The same error could be reproduced by disconnecting the vacuum to the turbo. The boost control worked, altering the vacuum to the turbo, and when tested with a voltmeter, you could see the voltage change, as well as the duty cycle. Unplugging the solenoid set an open circuit error. However, when road testing, you could see that the vacuum didn’t relate the percentage requested by the ECU intermittently, even without the fault active.

According to the customer, the issue started after an EGR recall. This information sent us down the wrong track. I wanted to see if the low- or high-pressure EGR was active when the fault set, so I drove the vehicle for 300 miles with a data logger connected in an attempt to capture more data, and it finally happened. I had not been able to reproduce the fault during those first 300 miles, but I could see that the boost did not always follow the set point, although it wasn’t far enough away to set the fault. This led me to think it was due to the turbo sticking. It was only after I watched Frank Massey’s video – which looked at the percentage commanded by the ECU – and compared it to the difference in vacuum, that I saw that it was low boost only in the mid-range commands (Fig.2).

I connected the PicoScope to the control solenoid and discovered that it took almost 50V to operate a 12V control solenoid. The feed to the valve was sufficient from the fuse with only battery voltage, and wiring to the ECU on the control wire was all good, as well as having a new ECU.

When I checked the ECU supplies, I found that one of the feeds was missing; the wire had been rubbing on the ABS pump and had broken. Without a good power supply, the ECU couldn’t control the valve correctly, and at around 70% operation, the vacuum to the turbo was too low, which meant that it would under-boost. The turbo didn’t have a position sensor on it, so the ECU was not informed that the turbo was in the incorrect position.

Every day is a school day as they say, and this is one I won’t forget in a hurry.