Train4Auto Consultancy’s Steve Carter takes a look at a Fiat Ducato with Bosch EDC 15C2 EMS and the issue of non-starting after a new engine fitment.

Common rail diesel engines have been in production for several years now, and many independent garages are probably seeing more and more of them as the owners pull away from dealer servicing. This case study involves a Fiat Ducato, but could also be relevant to any common rail diesel-powered vehicle.

This particular vehicle had, unfortunately, been driven through a flooded road when the inevitable catastrophic engine failure occurred: the number two con-rod had gone straight through the block.

Refusing to start

The garage that had been tasked with replacing the engine obtained an identical second-hand engine to replace the failed one. However, when the vehicle refused to start, they had some basic vehicle diagnostics which appeared to interrogate the vehicle’s engine management system. However, unbeknown to them, it was in fact using an EOBD protocol to do so, and the scan suggested that there were no fault codes present. The actual system on this vehicle was a Bosch EDC 15C2.

They attempted to measure the high-pressure pump output using a sealed rail kit to confirm they had sufficient rail pressure to trigger the injectors. During cranking, they had over 300 bar, more than sufficient pressure to start the engine. At this point they were beginning to run out of ideas so this is where I got involved with helping to rectify the problem. My first thought was to attempt to interrogate the vehicle’s engine management system using the Bosch EDC specific programme, at which point a fault code was retrieved: “Crankshaft position sensor; signal improbable”.

It should be noted that this is not a ‘P’ code, so is non-compliant under the EOBD protocol and, for your reference, diesel-powered vehicles did not have to conform to EOBD protocol before 2005. Remember EOBD is just for faults that affect emissions of the vehicle. We proceeded to evaluate the serial live data while cranking the vehicle. I was particularly interested in the engine speed and the high pressure rail value. Although the garage had confirmed there was sufficient pressure at the pump, it was still worthwhile to confirm that this was being seen by the engine EDC as well.

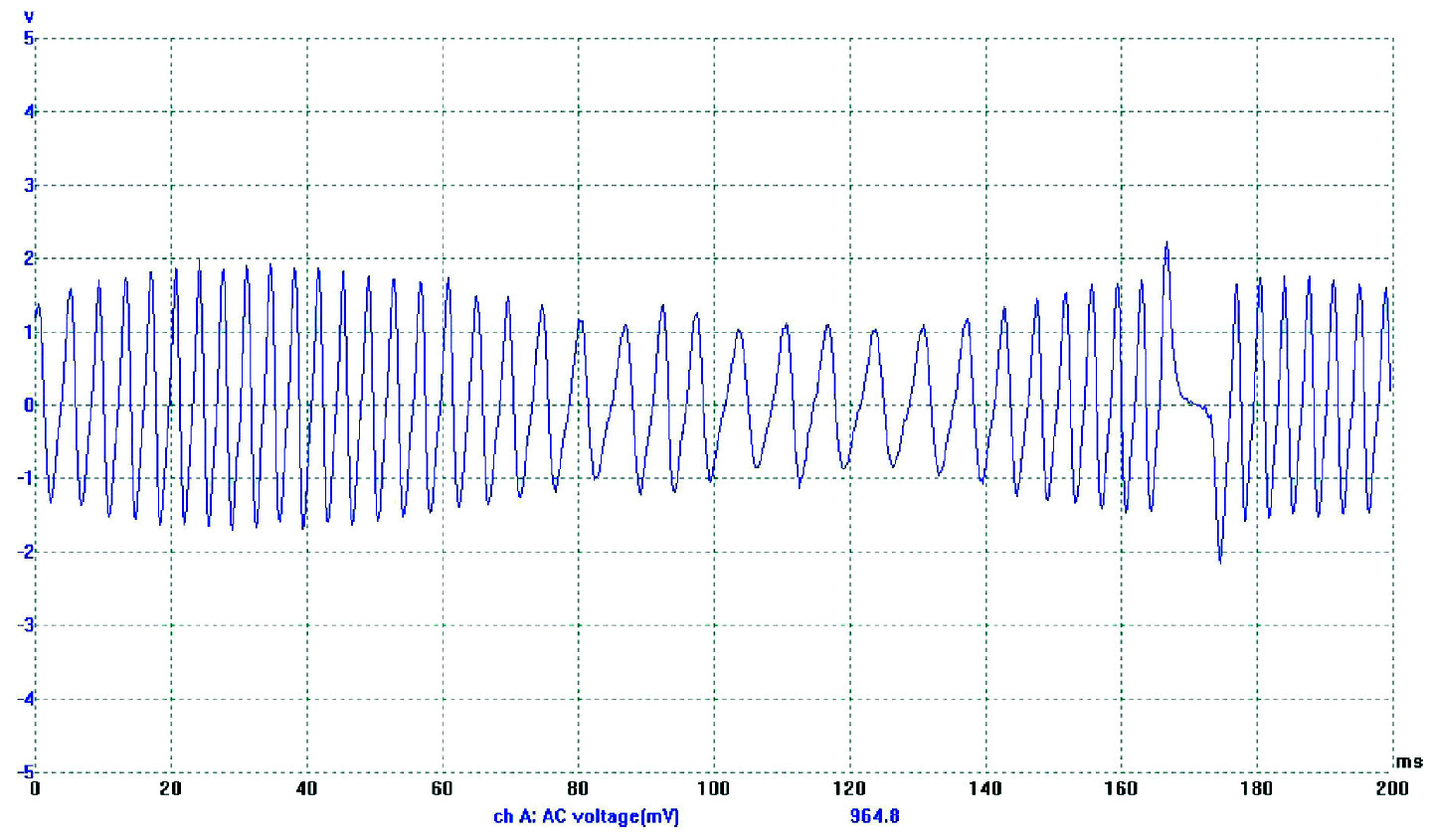

The rail pressure was in line with their previous test figures, confirming that the high-pressure pump, rail sensor and associated wiring to the EDC were in good order. As for the engine speed, this was a different matter; although we had a very stable engine cranking, the actual RPM indicated by the serial diagnostics ranged anywhere from 50 to 200 RPMs, thus confirming the crankshaft sensor as the potential problem. At that point the garage was ready to order a replacement crankshaft sensor. However, I wasn’t so sure and asked for a few more minutes with the vehicle. A quick scoping of the crankshaft sensor provided some useful information.

Sensor output

As you can see in the scope trace image (see Fig 1), the output of the sensor is just too low, with the maximum peak-to-peak being just below 2V, where in reality there should be at least 4V, if not 6. This was obviously the reason why the vehicle would not start and was the cause of those extreme RPM readings on live data.

The engine had been supplied in good working order from a reputable supplier. On further discussions with the garage, it transpired that although this was the same engine, it had been fitted to a different gearbox, and they were still using the original gearbox. On further investigation, it became clear that although the engines were nearly identical, they had one main difference – the flywheel.

If the engine had been used in conjunction with its original gearbox, then this problem would never have arisen. But they had used it with the vehicle’s original gearbox, which had a slightly different fixing/profile for the crankshaft position sensor. This resulted in the sensor being just under 2mm further away from the flywheel, leading to the erratic RPM reading and scope trace. The solution to the problem, therefore, was to exchange the flywheels.

As you can see from this example, more diligence and understanding of your diagnostic readings is paramount for modern common-rail diesel engines.